Online Dating Sucks – It’s Not Just You, It’s Us

I spent the better part of a decade online dating. I would enter into a relationship, it would go sideways because I chose a partner that was ill-equipped for love, and I would jump right into the tinder/bumble/hinge/okcupid pool. After an incident where I fell heartbreakingly, breath-stealingly, in love with a sex addict, I promised to take two years to myself. I did not. I jumped right back into the hot mess of online dating. I spent months getting horrible first messages, feeling wildly insecure, and losing faith that finding love was possible.

Was it me? Was I broken? Was there something about my existence that triggered hypersexual messages and shallow connections? Well, no, but yes. It’s complicated.

Online dating is a wonder of our time. Dating apps allow us to form connections, but it reproduces the very worst parts of social inequality.

Some people find meaningful connections. More people find solace in screenshots they share with their friends. These days you can’t operate a dating app without paying for a premium subscription service to swipe endlessly in your search for potential lovers. Tinder, and apps like it, provide a dating marketplace. We shop for potential partners, navigating dating apps as consumers looking for our best match or a worthwhile investment – capitalism reproduced in the microcosm that is our bedrooms. Just like in everyday life, the way capitalism organizes the social world reproduces major forms of inequality and isolates us further from each other.

Is shopping for love innately bad? It depends on how you view it. The online dating market in the United States is slated to make 1.35 billion dollars in 2023. 17.6% of people in the United States are on dating apps, a whopping total of 58,658,610 people. ( Statista https://www.statista.com/outlook/dmo/eservices/dating-services/online-dating/united-states) Online dating algorithms are subject to market analysis as researchers determine how to maximize matches (Jung et al. 2021). The entire premise of online dating necessitates rank order to establish what kind of people you are interested in. Boyd and Yoganarasimhanb (2021) argue that online dating apps now replicate centralized matching markets. Meaning, when you are looking for your next hookup, FWB, toxica, or a lifelong soulmate, you are recreating the stock exchange in your palm. In a stock exchange, buyers and sellers submit their orders and the exchange matches these orders based on specific rules and algorithms. The market acts as a central authority, ensuring that trades are executed efficiently and fairly.

In this instance, dating apps collect data from their millions of users and distribute that information over an algorithm using patterns and user input to be successful. These platforms deploy various tactics to foster emotional connections, such as gamification elements like swiping, instant gratification through matches and messages, and algorithms that continuously adapt to user behavior. An app in the United States paired up with marketing academics to determine the best way to achieve “assortment optimization” or how to keep giving you matches you actually like so you keep subscribing. Their job is to give you a hit of those good feelings (when you match) and to make sure you come back for more by analyzing your responses to partners and tracking changes. In 2017 I went to visit a best friend in Portland after a devasting breakup with a man I met on okcupid. I still remember the validation I felt when saw a notification that over 500 people had liked me in the 12 hours since I was back on Tinder. The marketing plot worked. Tinder premium was still reasonable and I could see who all wanted me if I deserved to feel validated — incredible job by the algorithm and marketing team.

Once again, I know, how bad could it be? What’s the harm of algorithms maximizing chances of success? It improves your ad experiences, and it helps get you some really rad impulse purchases off Instagram, what’s the big deal? Here is where sociologist Eva Illouz and her theory of emotional capitalism becomes relevant.

llouz argues that emotions have become commodities in capitalist societies. Emotional experiences and expressions, such as love, happiness, and self-esteem, are increasingly valued in the marketplace. Advertisements, media, and consumer culture often promote products or services by appealing to people’s emotional desires, promising that buying or consuming them will fulfill emotional needs. Emotional capitalism encourages individuals to engage in constant emotional management. Essentially, your emotional well-being is not an internal or communal process, rather your emotions are constantly regulated to meet social norms and make money.

Within the context of online dating, emotional capitalism comes into play as platforms capitalize on our deepest yearnings for love, intimacy, and connection. Dating apps and websites leverage our emotions to design persuasive user interfaces, targeted advertisements, and carefully curated profiles, all aimed at maximizing user engagement and profitability. We are compelled to project a certain image on social media, creating an idealized version of ourselves that aligns with societal standards of happiness, success, and desirability. I’m sure it’s hard to believe that as a woman getting “wanna fuck?” messages on Tinder five times a day that people are projecting their best selves, but that is the tension between needing to commodify oneself to make connections and the reality of who these people are. The person you swiped left for did not seem like the kind of person to message that they were an insatiable alpha looking for a tight-ass to jackhammer, but here you both are.

The thing about marketplaces is that they reflect the biases and inequalities that exist in our society. This is why you can be swiping to your heart’s content and see profiles that say “no blacks, no fats” and even in the gay community this expands to “no blacks, no fats, no femmes.” Our sexual preferences, and partner preferences, often reflect our political alignments and the dominant social beliefs about attractiveness and aesthetics. The insecurity and isolation felt while engaging in online dating is not an accident, it is the point. Capitalism does not exist in a silo, it is racialized, gendered, and straight. We know statistically that black and Hispanic populations make significantly less than their white counterparts. The gap is made even more dramatic when analyzed by gender and sexual orientation. The rift is still present in the online dating marketplace.

The success of online dating platforms hinges on their ability to create emotionally engaging user experiences. By keeping users emotionally invested and addicted to the platform, the marketing machinery behind online dating ensures continued engagement and subscription renewals while reproducing sexual and social norms that fuel inequality. Hanson (2022) found that online daters in their 20s integrated sexist and racist expectations into their communications and expectations with potential sexual and romantic partners. Women, in particular, bear the brunt of a system that objectifies, demeans and belittles them in the blink of an eye. The swipe culture reduces their worth to mere physical appearances, fueling a vicious cycle that undermines true connections and reinforces harmful gender norms. For women of color, the battle is two-fold. They navigate the intersecting oppressions of racism and sexism, forced to confront a relentless torrent of microaggressions, fetishization, and the erasure of their unique identities. The complexity of their experiences are lost amidst the monotonous sea of stereotypes, they strive to be seen and understood beyond the preconceived notions that make them illegible to others.

Dr. Celeste Curington, a sociologist at Boston University, found in her book that Black and Indigenous people of color were most likely to experience rejection on dating apps. black women especially experienced racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia on the apps. In her book, The Dating Divide: Race and Desire in the Era of Online Romance, Curington argues that there is digital sexual racism that is pervasive in online dating interactions. Specifically, digital sexual racism is how racial hierarchies are recreated through relationship desires and disseminated through the internet as they turn individual preferences into systematic segregation of partners and establish norms for online presentation. What she’s arguing is that in our interactions in online dating, we reproduce racism and sexism by preferring particular races, and specific forms of masculinity and femininity, and by excluding those who have been excluded by society.

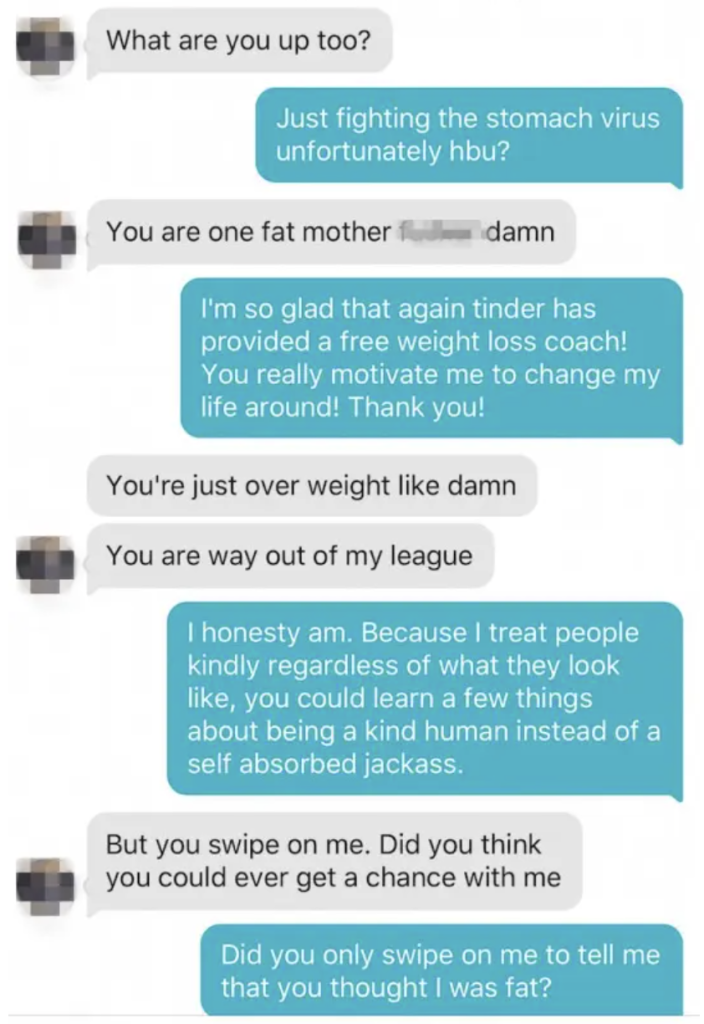

I am a fat person of color, and my dating experiences have ranged from fetishization to outright disgust. For fat women especially, the idea is that since they are seen as undesirable to much of the world they must be easy to convince to have sex. There are ongoing conversations about how fat women are the secrets men keep. Men are attracted to fat women, have sex with them, and love them, but the shame that deploys upon men who deviate from society’s expectations of desire, and masculinity, perpetuates emotional and social harm towards fat women in particular. Men will message me and tell me my body is disgusting, and then ask if I’m available to meet up that night.

The online dating industry thrives on creating and exploiting insecurities and desires for validation. The constant comparison with others and the pursuit of external validation through matches, likes, and messages can lead to emotional vulnerability and dependence on the platform for self-esteem. The commodification of emotions in capitalist systems can contribute to the reinforcement of beauty standards, including thinness, and perpetuate fatphobia. Advertisements often rely on body shaming or promoting unrealistic beauty ideals to trigger emotional responses and create market demand for weight loss products or services. Online dating is no different, women’s bodies especially have been commodified, and the pink tax, means we have to pay more to have our bodies policed and scrutinized.

I know, I’ve given data, explanations, and introductions to academic topics, and you may still be wondering so? everything comes at a cost. However, the trick of markets is that participation, engagement, and consumption contribute to cost (as well as institutional greed, but we will revisit that). Ultimately, the more desperate you are for connection the more money online dating apps make.

So. Let’s take a moment to reflect. Does online dating contribute to your well-being as much as it contributes to their profits?

- What do I gain from online dating?

- What do I lose from online dating?

- Does it cause more harm than it brings joy?

- How can I participate in online dating while being mindful of my own wellness?

- How can I participate in online dating and contribute to social wellness?

Many on TikTok and beyond brag about how they are attention whores. This is a fundamental reality for many people and it is not inherently a bad thing, but seeking external validation is not a replacement for self-respect. I know I sound like an asshole, but I am speaking from experience. I have ADHD, depression, and a whole slew of traumas that add up to a desperation for being seen. I want to be clear, there is not an inherent problem in needing/wanting validation from important people in our lives. My comments focus on the need to get attention from strangers that one is beautiful enough, fuckable enough, and interesting enough, to feel lovable and worthwhile.

I would delete the apps to work on myself. Then it would be midnight and I would want to feel like I meant something to someone and fifteen swipes later I would feel a buzz. I would talk to people and have some similar conversations (you’re hot, want to come over?) or the equally cringy, but right up my fixer-upper alley (here are all my problems, can you fix me?). I remember putting as many flaws as possible in my online profiles as I assumed it meant I would find more genuine connections. Yet I still went on first dates, anxious about my fatness, trying to hide that I sweat, desperate to make a connection that might help me feel less lonely. I learned quickly which parts of myself to commodify, and what parts were currency I could trade in.

My fatness had curves admired and desired by some. The Puerto Rican in me provided a smart ass mouth that was good at banter as long as I didn’t intimidate the people I was talking to. There is no shortage of emotional and social intelligence in my brain, so I was able to cater to people’s needs and vulnerabilities. Once I traded in these currencies, I had to negotiate with the microaggressions and racism that stirred up. I was the spicy Latina, I was the innately sexual, curvy, fat person that absolutely had to be good in bed (otherwise how else did I make up for existing while fat?) In a world with unlimited choices, I could ghost men who were TOO racist, TOO fatphobic, TOO inhumane. For people who are like me, raised as women, fat, and a person of color, there is an ongoing negotiation: how much emotional and social violence will I tolerate to find love or intimacy in a world that teaches people to hate my existence?

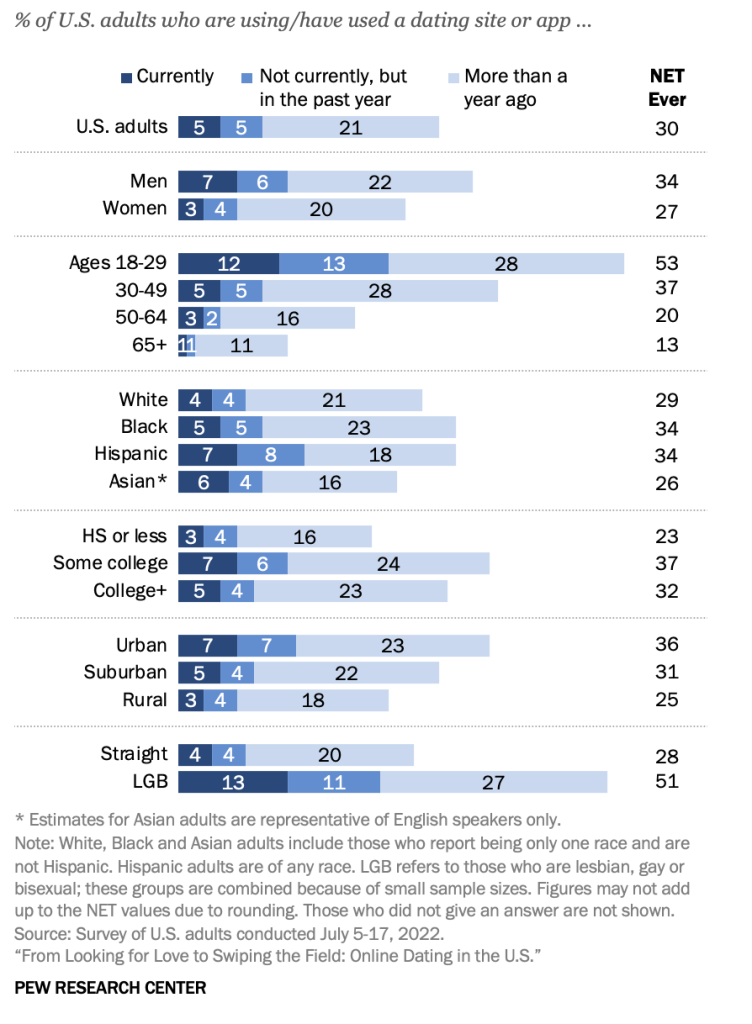

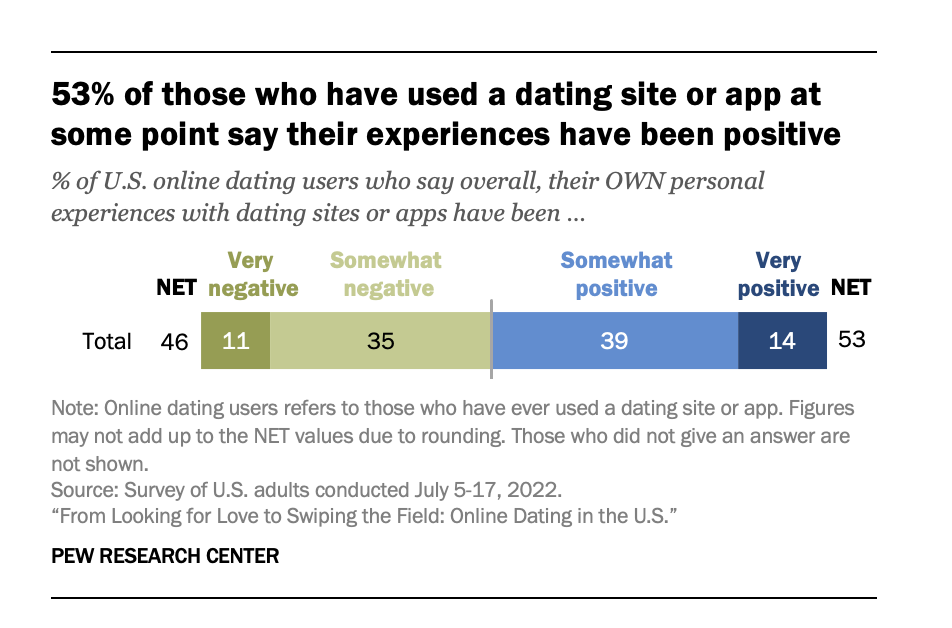

On all of the dating apps I tried my best to humanize myself often to be met with constant dehumanization, the weaponization of racist tropes, and a desire to mold myself into something easily consumable. My therapists often asked me why I didn’t believe I deserved better than the people I stayed with and made excuses for. My arguments often relied on the theme of “I see them as fully human.” A small irony in a social space where I was not given the same courtesy. I did fall in love. However, in the past three relationships I was in, I found that my partners were still swiping. They were looking for something better, something easier, something different. Some used Tinder, fetlife, and sex to create dopamine rushes that helped deal with self-hatred. Others engaged in lengthy conversations desiring to feel validated and seen, with no intentions to move beyond the feel-good attention. Pew data indicates that many people online are looking for love, but most of them are not very satisfied with the connections they are making online (https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2023/02/02/from-looking-for-love-to-swiping-the-field-online-dating-in-the-u-s/). The scarcity of genuine connections and meaningful conversations leaves them feeling isolated and overlooked.

Tinder, Bumble, Hinge, and all these dating apps make sincere connections possible. However, I believe it depends on the intentionality of the person using it. What have you done to advocate for the liberation of people with fewer privileges than you? If you have not done anything, why? On an interpersonal scale: Do you believe you’ve done the work of detangling your desires and attraction from systems of inequality? Do you understand what implicit biases you bring into your swipes? How does the way you’ve been treated show up in the way you negotiate intimacy and conversations with other people? If you aren’t thinking about these things, you should be. If you aren’t talking about these things in the community, you should be. Pew data show that Black and Hispanic users on dating apps are more likely to get unsolicited sexual messages and threats of violence. There is a clear power dynamic present in these exchanges, ones supported by capitalism, racism, sexism, and even colonialism.

Sincere engagement requires vulnerability, compassion, and emotional intelligence. It required leveraging legitimate intimacy against the shallowness of emotional capitalism. Humans have an incredible capacity for love, attachment, attraction, and compassion and we can bring it into our digital sphere. Emotional capitalism treats our ability to connect as a commodity, this is dangerous. Our ability to connect with each other and build community is the only way to have a future. So be yourself on Tinder, weird, human, messy, and awkward. Remember that perfect doesn’t make soulmates, or legitimate connections, and remember that managers serve a function in office spaces and bureaucracy, but your emotions deserve to be felt and seen not shrunken into oblivion.